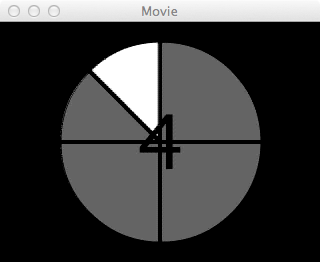

This first tutorial demonstrates one of the simplest yet most useful tasks you can perform with Jitter: playing a QuickTime movie in a window.

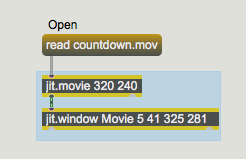

There are two Jitter objects in this patch: jit.movie and jit.window. The jit.window object automatically opens a window on your computer screen. The jit.movie object allows you to open an existing QuickTime movie, and begins to play it.

By default a jit.movie will begin playing a movie as soon as it opens it. (Alternatively, you can alter that behavior by sending a jit.movie object an message before opening the file, but for now the default behavior is fine.) Notice, however, that even though we've said that the jit.movie object is playing the movie, the movie is not being shown in the Movie window. Here's why:

Each object in Jitter does a particular task. The task might be very simple or might be rather complicated. What we casually think of as "playing a QuickTime movie" is actually broken down by Jitter into two tasks:

1. Reading each frame of movie data into RAM from the file on the hard disk

2. Getting data that's in RAM and showing it as colored pixels on the screen.

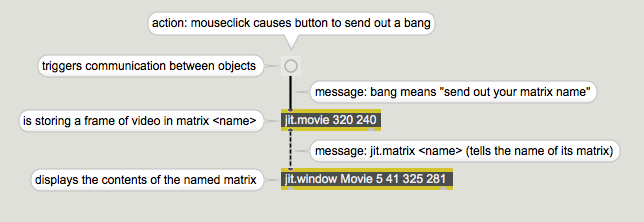

The first task is performed by the jit.movie object, and the second by the jit.window object. But in order for the jit.window object to know what to display, these two objects need to communicate.

How Jitter Objects Communicate

Causing Action by Jitter Objects

What causes one Jitter object to send a message to another object? Most Jitter objects send out a message when they receive the message or . (These two messages have the same effect in most Jitter objects.) The other time that an object sends out a message is when it has received such a message itself, and has modified the data in some way; it then automatically sends out a message to inform other objects of the name of the matrix containing the new data.

To restate the previous paragraph, when an object receives a message, it does something and sends out a message of its own. When an object receives or , it sends out a message without doing anything else.

So, in our example patch, the jit.movie object is "playing" the QuickTime movie, constantly storing the current frame of video, but the jit.window object will only display something when it receives a message from the jit.movie object. And that will only happen when jit.movie receives the message (or ). At that time, jit.window will display whatever frame of video happens to be currently playing in the movie (that is, the frame that's currently stored by jit.movie).

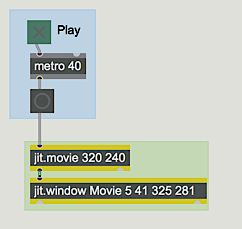

In order to make jit.window update its display at the desired rate to show a continuously progressing video, we need to send the message to jit.movie at that rate.

but we need to send it a each time we want to display a frame.

To summarize, jit.movie is continually reading in one video frame of the QuickTime movie, frame by frame at the movie's normal rate. When jit.movie receives a , it communicates the location of that data (that single frame of video) to jit.window, so whatever frame jit.movie contains when it receives a is the data that will be displayed by jit.window.

Arguments in the Objects

The jit.movie object in this tutorial patch has two typed-in arguments: . These numbers specify the horizontal and vertical (width and height) dimensions the object will use in order to keep a single frame of video in memory. It will claim enough RAM to store a frame with those dimensions. So, in the simplest case, it makes sense to type in the dimensions of the movie you expect to read in with the message. In this case (since we made the movie in question ourselves) we happen to know that the dimensions of the QuickTime movie countdown.mov are 320x240.

If we type in dimension arguments smaller than the dimensions of the movie we read in, jit.movie will not have claimed enough memory space and will be obliged to ignore some of the pixels of each frame of the movie. Conversely, if we type in dimension arguments larger than the dimensions of the movie we read in, there will not be enough pixels in each frame of the movie to fill all the memory space that's been allocated, so jit.movie will distribute the data it does get evenly and will fill its additional memory with duplicate data.

The jit.window object has five typed-in arguments: . The first argument is a name that will be given to the matrix of data that jit.window displays. That name will also appear in the title bar of the movie window. It can be any single word, or it can be more than one word if the full name is enclosed between quote characters. The next two arguments indicate the x,y screen coordinates of the upper-left corner of the display region of the movie window, and the last two arguments provide the x,y coordinates of the lower-right corner of the display region. (Another way to think of these four numbers is to remember them as the coordinates meaning "left", "top", "right", and "bottom".) We have chosen these particular numbers because a) they describe a display region that is 320x240 pixels, the same size as the movie we intend to display, and b) when we take into account the dimensions of the window borders, title bar, and menu bar that the OS imposes, the entire window will be neatly tucked in the upper-left corner of our useable desktop. (It's possible to make the window borders and title bar disappear with a message to jit.window, but the default borders are OK for now.)

We have typed the value of in as an argument to metro to cause it to send out 25 messages per second. The QuickTime movie actually has a frame rate of exactly 24 frames per second, so this metro will trigger the jit.movie object frequently enough to ensure that every frame is made available to jit.window and we'll get to see every frame.

The jit.movie object actually understands many more messages besides just (way too many to try to explain here). In the upper-right corner of the Patcher window, we've included an example of one more message, simply to demonstrate that the progress of the QuickTime movie can be controlled in jit.movie independently of the rate at which the metro is sending it messages. The message , followed by a number, causes jit.movie to jump immediately to a specific time location in the movie.

To play a QuickTime movie, use the jit.movie object to open the file and read successive frames of the video into RAM, and use the jit.window object to display the movie in a separate window. Use typed-in arguments to specify the dimensions of the movie, and the precise coordinates of the display area on your screen.

Summary

Jitter objects communicate the information about a particular frame of video by sending each other the name of a matrix—a place in memory where that information is located. When a Jitter object gets a matrix name, it performs its designated task using the data at that location, then sends out the name of the modified data to other Jitter objects. Almost all Jitter objects send out a name (in a message) when they receive the message (or ). Thus, to show successive frames of a video, send messages at the desired rate to a jit.movie object connected to a jit.window object.

See Also

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Working with Video in Jitter | Working with Video in Jitter |

| Max Basics | Max Basics |

| jit.movie | Play a QuickTime movie |

| jit.window | Display data in a window |

| metro | Output a bang message at regular intervals |