Tutorial 35: Lighting and Fog

Lighting—the illumination of objects in the real world—is a very complex subject. When we view objects, our eyes focus and detect photons throughout a range of energies that we call visible light. Between their origin in the Sun, lightning, fireflies or other light sources and our eyes, they can travel on a multitude of complex paths as they are reflected from or refracted through different materials, or scattered by the atmosphere. Our computers won’t be dealing with this level of complexity anytime soon, so OpenGL simplifies it greatly.

The OpenGL Lighting Model

Lighting in OpenGL is based on a very rough model of what happens in the real world. Though very crude compared to the subtlety of nature, it is a good compromise, given today’s technology, between the desire for realism and the cost of complexity.

We have already seen how colors in OpenGL are described as RGB (red, green and blue) values. The lighting model in OpenGL extends this idea to allow the specification of light in terms of various independent components, each described as RGB triples. Each component describes how light that’s been scattered in a certain way is colored. The continuum of possible real-world paths is simplified into four components, listed here from most directional to least directional.

The specular light component is light that comes from a certain direction, and which also reflects off of surfaces primarily in a given direction. Shiny materials have a predominant specular component. A focused beam of light bouncing off of a mirror would be a situation where the specular component dominates.

Diffuse light comes from one direction, but scatters equally in all directions as it bounces off of a surface. If the surface is facing directly at the light source, the light radiation it receives from the source will be the greatest, and so the diffuse component reflected from the surface will be brightest. If the surface is pointing in another direction, it will present a smaller cross-section towards the light source, and so the diffuse component will be smaller.

Ambient light is direction-less. It is light that has been scattered so much that its source direction is indeterminate. So it appears equally bright from all directions. A room with white walls would be an environment with a high ambient lighting component, because so many photons bounce from wall to wall, scattering as they do so, before reaching your eye.

Finally, emissive lighting is another component that doesn’t really fall anywhere on the directionality scale. It is light that only reaches your eye if you’re looking directly at the object. This is used for modeling objects that are light sources themselves.

These components are used to describe materials and light sources. Materials made of specular, diffuse, ambient and emissive components are applied to polygons to determine how they will be colored. Polygons with materials applied are lit based on their positions and rotations relative to light sources and the camera, and the specular and diffuse properties of light sources, as well as the ambient light component of the scene.

Getting Started

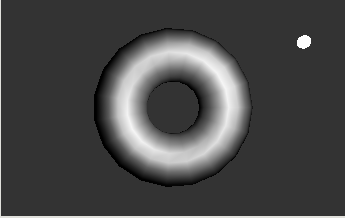

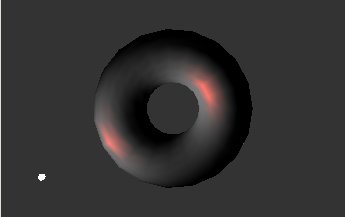

You will see a flat gray torus and a small white circle in the jit.pwindow object. The jit.gl.gridshape object in the center of the tutorial patch draws the torus. The other jit.gl.gridshape object in the patch, towards the right, draws the white circle. The scene is all presented in flat shades because lighting is not yet enabled.

Lighting is off by default for each object, so you must enable it. The same goes for smooth shading. When you set these two attributes, you will see the torus go through the now-familiar progression (assuming you’ve been doing these tutorials in order) from flat shaded to solid faceted to solid and smooth. When you set the attribute to 1, you won’t see any change, because its default value is already .

The attribute is provided in Jitter so that you don’t always need to specify all the components of a material just to see an object lit. When the attribute of an object in the GL group is on and lighting is enabled for the object, the diffuse and ambient material components for the object will be set to the object’s color, and the specular and emissive lighting components are disabled. This resulted in the flat gray torus we saw initially. In this tutorial, though, we want to see what happens when all the lighting components are specified explicitly, so we have turned the attribute off.

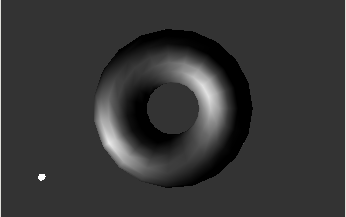

The image that results appears shinier, because the material applied to the torus now has a specular component.

Moving the Light

The jit.gl.gridshape object drawing the white circle has a jit.gl.handle object attached to it. As we’ve seen before this allows you to move the circle by clicking and dragging over it with the command key held down. By dragging with the option key held down, you can move the circle towards and away from the camera in the scene.

The x, y and z position values from the jit.gl.handle object are also routed to an unpack object, which sends them to number box objects for viewing. A pak object adds the symbol to the beginning and another value to the end of the list. This message is sent to the jit.gl.render object to set the position of the light in the scene. Note that the light itself is not visible, except in its effect on other objects. The white circle is a marker we can use to see the light’s position.

The light source moves with the white circle. If you move it to the right place, you can create an image like this.

The diffuse and specular components of the light are combined with the diffuse and specular components of the material at each vertex, according to the position of the light and the angle at which the light reflects toward the camera position. When you move the light, these relative positions change, so each vertex takes on a different color.

Jitter attempts to prevent you from worrying about this as much as possible, in a couple of ways. First, most objects in the GL group have normals associated with them. These are calculated by the object that does the drawing. The jit.gl.gridshape object is one example. If its shape is set to a sphere, it generates a normal at each vertex pointing outwards from the center of the sphere. Each shape has a different method of calculating normals, so that the surfaces of the various shapes are smooth where curved, yet the edges of shapes like the cube remain distinct and unsmoothed.

Secondly, if you send geometries directly to the jit.gl.render object in matrices, the jit.gl.render object will automatically create normals for you to the best of its ability. If you draw a connected grid geometry by sending a matrix followed by the or primitives, the generated normals will be smoothed across the surface of the grid. If you send a matrix using other primitives such as triangles, jit.gl.render will make no attempt to smooth the vertices, but will generate a normal for each distinct polygon in the geometry.

If you want to make your own normals, you can turn automatic normal generation off with by setting the attribute of the jit.gl.render object to .

Tutorial 37, "Geometry Under the Hood" describes how vertices, colors and normals can be passed in Jitter matrices to the jit.gl.render object. For more information on how to specify normals for geometry within a matrix, please refer to the Jitter Appendix B in this publication.

Specular Lighting

Let’s change the specular components of the lighting to get a better feel for them.

The swatch object sends it output as a list of three integers from to . The vexpr object divides each integer in the list by to generate a floating-point value in the range to , which is the range Jitter’s OpenGL objects use to specify colors.

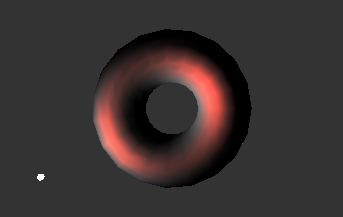

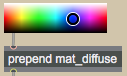

The highlights of the image now have a red color. The specular component of the light source, which is currently white, is multiplied by the specular material component to produce the color of the highlights.

The red, green and blue values of the specular light source are multiplied by the red, green and blue values of the specular material component, respectively. So if the light source component and the material component are of different colors, it’s possible that the result will be zero, and no highlights will be generated. This more or less models the real-world behavior of lights and materials: if you view a green object in a room with red light, the object will appear black.

The attribute of objects in the GL group is an important part of the material definition. It specifies to what extent light is diffused, or spread out, when it bounces off of the object. To model a mirror, you would use a very high value. Values of approximately to are useful for making realistic objects.

This makes the contribution of the specular lighting components much smaller in area. Accordingly, you can see the specular lighting in red quite distinctly from the diffuse lighting, which is still gray.

Diffuse Lighting

Let’s manipulate the colors some more to see the effect of the diffuse component.

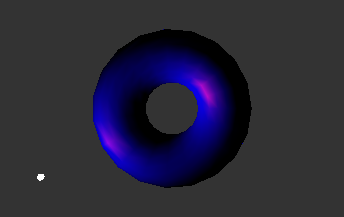

The diffuse reflections from the torus are now blue, and the highlights are magenta. This is because the color components of an object’s material, after being multiplied with the lighting components depending on positions, are added together to produce the final color for the object at each vertex.

Ambient Lighting

We have yet to change the ambient component of the object’s material. Currently, this is set to its default of medium gray, which is multiplied by the dark gray of the global ambient component to produce the dark gray areas of the torus in the picture above. The global ambient component is multiplied by all ambient material components in a scene, and added to each vertex of each object. You can set this with the attribute of the jit.gl.render object.

The ambient material component is multiplied by the global ambient illumination component to make the dark green areas that have replaced the gray ones.

The moveable light in the scene has an ambient component associated with it, which is added to the global ambient component. To change this, you can move the circle in the swatch object above the prepend object. If you change this to a bright color, the whole object takes on a washed out appearance as the intensity of the ambient component gets higher than that of the diffuse component.

That’s Ugly!

A green torus with blue diffuse lighting and magenta highlights is probably not something you want to look at for very long. If you haven’t already, now might be a good time to play with the color swatches and come up with a more harmonious combination.

Note that control over saturation isn’t provided in this patch for reasons of space. But it’s certainly possible to specify less saturated colors for all the lighting and material components.

Directional vs. Positional Lighting

The moveable light in a scene can be either directional or positional. In the message sent to jit.gl.render, the value decides whether directional or positional lighting is used. If is zero, the light is a directional one, which means that the values , and specify a direction vector from which the light is defined to come. If is nonzero, the light is a positional one—it illuminates objects based on its particular location in the scene. The position of the light is specified by the homogeneous coordinates , and .

Positional lights are good for simulating artificial light sources within the scene. Directional lights typically stand in for the Sun, which is so far away that moving objects within the scene doesn’t change the angle of the lighting perceptibly.

Notice how the lighting shifts across the surface of the torus as it moves, if the torus moves past the general vicinity of the light. You may have to move the light’s position to see this clearly.

Now, notice that because directional lighting is off, the lighting no longer shifts when the object changes its position.

Fog

Like other aspects of lighting, the simulation of fog in OpenGL is primitive compared to the real-world phenomenon. Yet, it offers a convenient way to a richer character to an image. OpenGL fog simply blends the color of the fog with the color at each vertex after lighting calculations are complete, in an amount that increases with the object’s distance from the camera. So faraway objects disappear into the fog.

In Jitter, fog can be turned on or off for each object in the GL group by using the fog attribute. Some objects in a scene can have fog applied to them while others don’t.

You should see the torus receding into the fog as it gets farther from the camera, assuming the “p ” subpatch is still active.

Now, when the torus gets farther away, it doesn’t disappear. Rather, it turns bright red. Fog makes faraway objects tend toward the fog color, which may or may not be equal to the background color. Only if the fog color and the color of the background are nearly equal will realistic fog effects be achieved.

If you like, try manipulating the other parameters of the fog with the number box objects above the message.

Summary

We have described OpenGL’s lighting model and its implementation in Jitter in some detail. We discussed the specular, diffuse and ambient components of the GL lighting model, how they approximate different aspects of a real world scene, and how they combine to make an image. The distinction between positional and directional lighting was introduced. Finally, we saw how to add fog to a scene on an object-by-object basis.

See Also

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| Working with OpenGL | Working with OpenGL |

| GL Contexts | GL Contexts |

| jit.gl.gridshape | Generate simple geometric shapes as a grid |

| jit.gl.handle | Use mouse movement to control position/rotation |

| jit.gl.render | Render Jitter OpenGL objects |

| jit.pwindow | Display Jitter data and images |

| swatch | Choose a color |

| vexpr | Evaluate a math expression for a list |